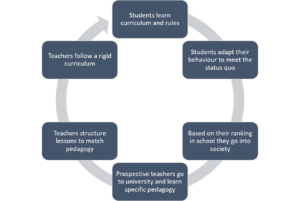

If you fit into the status quo then you are probably either comfortable with it, or oblivious to it. I have found myself previously in that comfortable category. Whereas the students that do not meet the status quo they are often excluded by peers, less successful in the class room setting or even ignored, which in turn affects their trajectory into society (Gatto, 2013). What I never had thought of prior to the education program was how the “acceptable” way of living and learning was defined. One source of this definition is written by mass schooling (Gatto, 2013). The structure of mass schooling allowed for the development of a vicious cycle whereby it controls students, teachers, and citizens. The purpose of this behavioural and intellectual control makes people predictable, easier to advertise to, and easier to manipulate (Gatto, 2013). The way in which mass schooling substantiates the cycle is by fixing expectations for teachers, students, and curriculum. Achieving these expectations positively reinforces the system. However, what I have learned so far in in the education program, is that the vicious cycle of mass schooling needs to be broken to make the learning environment accessible for all students. In addition, it can be done with small changes to the education of teachers and viewing curriculum as a praxis.

The Vicious Cycle

The first point in the cycles begins with the student. A student must adapt their behaviour to meet several expectations, the first of which is towards authority (Gatto, 2013). Students learn to follow the rules and learn material outlined by the teacher without a critical thought as to why. Secondly, students must match, or meet the social expectations of their peers so that they fit in (Gatto, 2013). Thirdly, they must work hard in school to learn the curriculum in the prescribed way to be considered successful. If a student does not meet these behavioural expectations, then they will be outcast. This behavioural expectation allows students themselves and teachers to rank their peers based on their performance. Thereby the structure of mass schooling forces children to hide individuality and inhibit creativity in order to be “successful”. Based on these rankings’ students are set on a trajectory outside of school to fill a predefined role in society (Gatto, 2013).

To follow, the students set on the trajectory to become educators bring their experience in school and ingrained values to post-secondary education. The new teacher candidates’ prior beliefs about education is one factor at this stage that positively enforces the cycle. Moreover, the education programs itself enforces the cycle by teaching educational philosophies that align with mass schooling and candidates’ previous experiences. For example, idealizing the teaching philosophy of essentialism leads to practices involving a teacher-centered, content-based, delivery of essential information to students (Sahin, 2018). Without allowing teachers to build their own pedagogy, they cannot express their own individuality. Controlling the definition of what a teacher should be reinforces the vicious cycle.

In addition, even if a teacher has a unique teaching philosophy, they were bound to a rigid curriculum which controlled the information and depth to which it was taught. This occurred when curriculum was structured as a product (Smith 1996, 2000). The way that curriculum was viewed also affects the way that kids learn in the classroom. When curriculum was viewed as a product, focus was centered around the objectives leaving no flexibility or room for extension, and a lot of memorization (Smith 1996, 2000). Furthermore, when constrained to teaching per the curriculum, it limits teachers’ abilities to adapt the information to the present students. Moreover, it leads to a regiment with less opportunity for creativity and individuality. Controlling the curriculum brings the vicious cycle back to the beginning of students learning in the same away again and the same kids left out.

Breaking the cycle

There are a couple places within this the cycle where modification can lead to impactful change for students’ experiences in school. The first of place of modification is how teachers are trained. So far, I have learned that teachers need to develop their own unique identity as an educator. As a result, this unique identity will model the importance of individuality to students. One way to do this is to introduce different kinds of teaching philosophies. Two that I have identified with are Progressivism, and the First People’s Principles of Learning. Progressivism values student-centered teaching, inquiry, and interest (Cohen & Gelbrich, 1999). The First People’s Principles of learning values community, storytelling, student-centered teaching, building off our strengths, and individuality (Chrona, 2016). I feel that the inclusion of these two philosophies to my own practice and that of other teachers will make classrooms a warm and welcoming place for student to explore their identity and the curriculum in a way that is unique and meaningful for themselves. It also gives students a way to investigate and think critically and innovatively about the information that is presented.

A second place of change is in the content and structure of the curriculum. Changing the way that curriculum is structured will have an impact on the way that children learn and develop because it will change the possible ways that the information is presented. One innovative way of structuring a curriculum is by viewing it as a praxis. This means that the curriculum is a flexible, changing, mouldable set of big ideas that can be implemented in many ways (Smith 1996, 2000). The flexibility of the curriculum allows teachers to modify the projects and assignments towards interests of children and has the room for students to explore their learning. Furthermore, the inclusion of indigenous knowledge into the curriculum provides a layer of context to the information. If content is contextualized, it means it is more applicable to students through connection of people, place, and land that is significant to them. This can help students understand the meaning of content and its relevance. In addition, including indigenous knowledge in the curriculum and viewing it as a praxis allows for opportunities to connect students learning with community. Thus, there is a chance to apply what they have learned to the community which in turn fosters critical thinking and problem-solving skills in their own unique way.

Conclusion

Overall, the cyclic nature of mass schooling has been an effective way to educate large numbers of students with considerably few teachers, with an inferred goal of assimilation, and control. These methods came at the expense of innovation, growth, and a lot of student’s well-being. The acknowledgement of this cycle is the first step into figuring out how we, as teacher candidates, can work towards improving the education system. Therefore, we can start to structure our pedagogy, and think creatively in how to interact with the curriculum in order to best support the individuals who are in our future classrooms. When we make these changes then ALL students will be able to develop to the best of their ability; think critically and innovatively; and make lasting connections to the information, teachers, peers, and community.